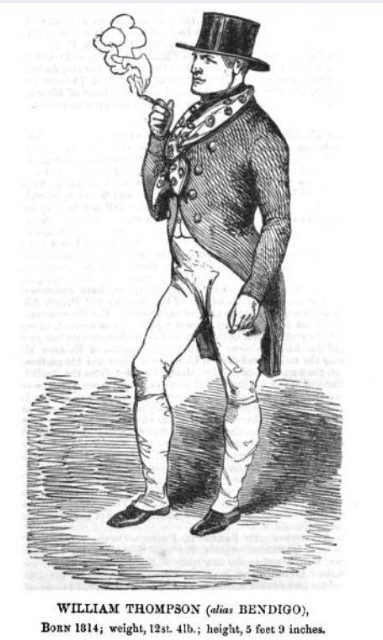

It is unfair to compare Bendigo to other boxers with whom we might be more familiar. In Bendigo’s time, the technology we enjoy today was not there for him. The invention of film allowed us to get to know boxers more personally.

Facial features, fighting style, and personality are all aspects we can find out about regarding any boxer after the 1900s.

When it comes to Bendigo, we are not that spoilt. We must rely on articles, books and sketches. Owing to this, it seems more natural to use more current fighters to get a better feel for past pugilists and that is exactly what the New York Times did in 1935.

John Kieran, was a sportswriter for the New York Times and would go on to become a Hall of Fame sports broadcaster and a regular face on US television. His article in 1935 had the headline.

“Bending Backward From Baer to Bendigo”

“Here. Read about Bendigo. He must have been the Max Baer of old England” cheerfully declared a gentleman as he dropped a hefty book onto Kieran’s office desk.

That book was the famed “The Story of Boxing” by Trevor Wignall. In the book, which covers many 19th century old British bare-knuckle boxers, it describes Bendigo as a “Pugilist, Harlequin, and Revivalist”. It is the word ‘Harlequin’ that really grabs Kieran’s attention as to what the cheerful fellow was suggesting.

The Clown Prince of Boxing

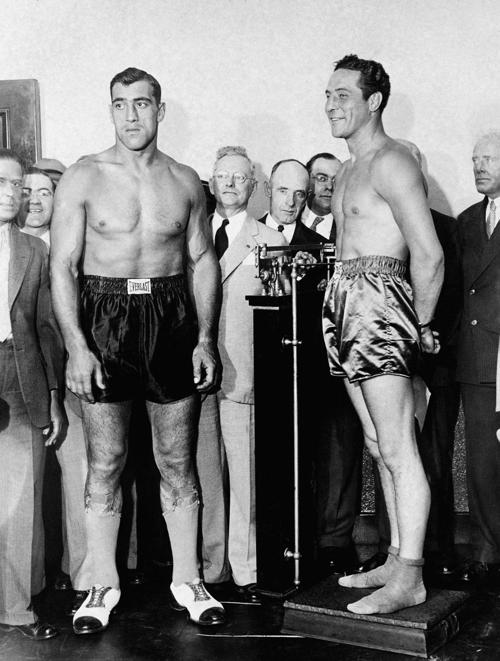

At the time of New York Times article, Max Baer (the ‘Clown Prince of Boxing’) was the heavyweight champion of the world.

Baer was a remarkable character who enlightened America during a time the country was rocked by the Great Depression.

He was an old school American heart-throb, an eccentric, a joker, and sadly misunderstood. (Hollywood’s depiction of Baer in the film ‘Cinderella Man’ is quite inaccurate).

The Nottingham Jester

Bendigo was also a very colourful character.

Many people during his fighting career referred to him as the ‘Nottingham Jester’ and every article you can read about him describes him as being eccentric.

Bendigo was a master at taunting his opponents. He would dance around them, pull silly faces, reciting rude rhymes, calling his rival ‘a big chucklehead’. The crowds loved it.

When Bendigo retired from the prize ring, he began to enter a particularly dark time in his life, which involved too many pubs and prison cells. However, he would turn his life around when a priest would grab his attention with the story of David and Goliath. Bendigo replied,

‘I should like to know more about that David bloke. He must have been a good’un for a lightweight’.

Bendigo

A notable example of Baer’s mischief and jest was before his world title fight with the ‘Ambling Alp’ Primo Carnera, he sneakily plucked a hair from Carnera’s chest as if it was a garden daisy and said “He loves me!”. He then managed to grab another before the man mountain realised what he was doing and said “He loves me not!”, reporters present were rolling around laughing.

Kieran suggests that the Bendigo comparison is perhaps a lazy one and that he could equally be likened to ‘The Fighting Marine’ Gene Tunney, who twice beat the famous Jack Dempsey and middleweight king Mickey Walker. Interestingly, they both had a history of saving people from drowning, which Bendigo did numerous times whilst fishing on the River Trent in Nottingham.

This heroic act of saving a drowning person was mentioned to Max Baer whilst he was training at Asbury Park. He cheekily responded that ‘the waves were pretty high’ and that he would not attempt to rescue anyone unless they were a ‘prominent person like Johnny Weissmuller’. Maybe this was another example of the boxer’s jest. (Johnny Weissmuller was an Olympic Swimmer who became more well known in the 1930’s as an actor).

Another aspect of the Bendigo-Baer comparison that Kieran perhaps overlooks in his article is that both fighters had to overcome significant size disadvantages to win their championships.

Max Baer overcame four inches in height, four inches in reach and nearly a four stone weight disadvantage against the colossal Primo Carnera, who stood 6ft 5inches.

Bendigo was also the much smaller man in his battles against Ben Caunt who was 6ft 2 inches – a giant of the time when the average height of a man was 5ft 5 inches. Bendigo’s height was chalked up at just under 5ft 10 inches and he would also enter the ring around the 11st 11lb mark. He would look like a snack stood next to Caunt ‘The Torkard Giant’, as he entered the ring weighing up to 18st.

The main aspect that I think links Baer and Bendigo is that they both stood out and entertained people. They were different. They made the sport better and that is why they both have their names in the Boxing Hall of Fame.

I mentioned earlier that Baer was misunderstood and also misrepresented in the film ‘Cinderella Man’. The film seems to portray him as a killer. In my opinion, Baer’s manager’s view has to be considered. He said that Baer’s ‘Heart was too big for his fists’.

I invite readers to watch the Max Baer documentary called ‘Tender Hearted Tiger’ so you can decide in which thought league you stand.

Article written and researched by Jevon Patrick for the Bendigo Heritage Project