We took ‘Bendy’ our maquette of Bendigo back to the locations around what is now Milton Keynes, where preparations for the third and final fight between these bitter rivals took place. The purse and contract between Bendigo and Caunt had been agreed on 17th April, but it took five months for it to happen.

Bendigo took his training seriously. He always prepared thoroughly, and for longer than the three months that was generally expected of prize-fighters. Those putting up the prize money expected regular updates on their fighter’s preparation. Bendigo trained at Crosby near Liverpool. He was ready.

Caunt also prepared like he had never done before. His fight camp was near Hatfield, north of London, where he was a publican and living amongst the London Fancy. He had lost three stone and weighed just under 14 stone, a weight he had never previously achieved.

The fight had attracted a lot of public attention. Both were genuine and worthy contenders for the title and this would be the deciding contest between them.

Caunt’s physical size and Bendigo’s skill made the outcome harder to predict. There was also uncertainty about Bendigo’s damaged knee and that he was now thirty-three years old. There was so much ill-feeling between them. Neither would give an inch.

Big News

On Sunday 7* September, two days before the event, Bell’s Life announced:

‘The great tilting match between Ben Caunt (the present champion of England) and the renowned Bendigo who seeks to deprive him of the distinction which he has so hardily won and so honourably maintained, is to come off on Tuesday next within 70 miles of London. The precise ground on which ‘the lists’ are to be formed has not yet been selected.’

Bell’s Life

The paper went on to express concern that ‘every possible pain’ was taken to preserve order on the day. As usual an inner ring for the accommodation of the wealthy swells and Corinthians was to be formed twelve yards from the ropes. Rumours had been circulating that the Nottingham Lambs were planning to cut the ropes and break into the ring, if Bendigo appeared to be losing. In view of the Lambs’ customary conduct, this was a distinct possibility, yet Bell’s Life dismissed the rumours as ‘foolish threats’, believing a large contingent of ring stewards armed with whips would be able to repel all trouble-makers.

Police Interest

Bendigo arrived in Newport Pagnell on the evening of Sunday, accompanied by Jem Ward and Sam Merryman. The constabularies of Buckinghamshire and surrounding counties had been on full alert, as hordes of spectators descended on the area. Bendigo’s boisterous arrival was greeted by the large band of his supporters. Before long a constable arrived and announced that he had a warrant to arrest anyone attempting a breach of the peace.

Jem Ward immediately took Bendigo out of the village and installed him at a nearby farmhouse, where he remained until the morning of the fight. The Lambs and other followers from the Midlands, Sheffield and Liverpool, remained in Newport Pagnell. The locals must have disliked this invasion, but money was to be made and the police seemed interested in arresting only the main individuals, should it be necessary.

On Monday evening, Ben Caunt arrived at Wolverton railway station, two miles west of Newport Pagnell. He had travelled on the four o’clock train from Euston, having returned to London from his training base on the Sunday. As part of the build up he made an appearance at Tom Spring’s public house in Holborn, where he gave out two hundred handkerchiefs in his colours of orange with a blue border. The recipients were told to pay him a guinea each if he won, nothing if he lost.

Caunt, Spring and the rest of his party took lodgings at the Cock, an inn in the neighbouring parish of Stony Stratford, while Bendigo’s supporters continued to pour into Wolverton by the trainload.

These were the early days of rail travel and never again would the small station see as many travellers pass through as it did on those two days in September 1845.

Meanwhile, Bendigo’s followers, who some were described as ‘of a most questionable aspect’ set up base in Newport Pagnell. The first arrivals were put up at a coaching inn called The Swan Hotel, but it was not long before every available room, barn and outhouse was occupied for miles around. A man was considered lucky if he found a chair to spend the night in.

The locals soon realised that some of these ruffians had money to spend. Food and drink was sold at exorbitant prices. Carts and gigs and any form of transport, in all sorts of disrepair were hired out at a sovereign per person. Some of the more enterprising locals did six months’ business in a few hours. For the time being the Lambs had things their own way, terrifying the locals with their ‘leering swagger’ and their ‘heavy twigs’, a term used for a cudgel.

Caunt still had supporters from Nottinghamshire.The miners and farm hands who had supported him all his career, but as landlord of the Coach and Horses in St Martin’s Lane, he was now very much the London man-about-town. Most of his supporters from the capital travelled up on the morning of the fight.

Final Preparations

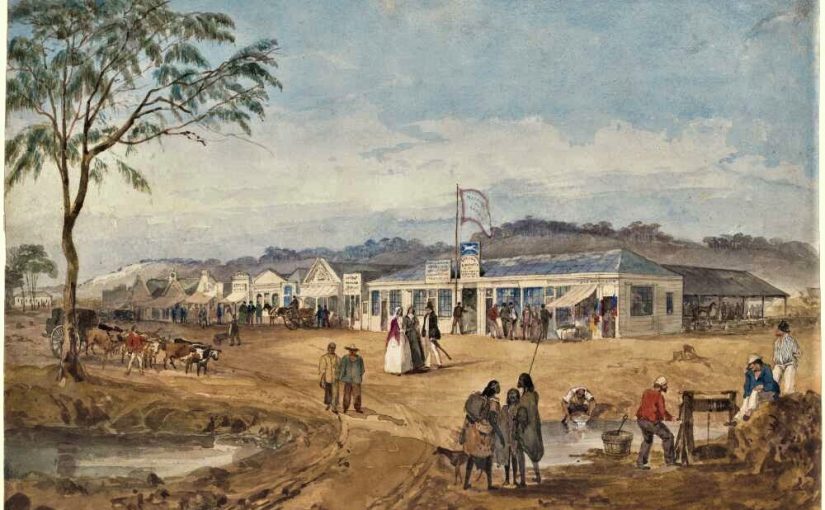

On Monday evening a meeting took place at the Swan Inn at Newport Pagnell, now trading as The Swan Revived and situated at 33 High Street, Newport Pagnell.

The Swan Inn. A former coaching inn, it provided good stabling and excellent hospitality for those traveling through Buckinghamshire to Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds. It was re-named the Swan Revived in 1952 after a major refurbishment.

Bendigo had Jem Ward with him. Ward was a former English champion from 1825 until his retirement in 1831 when he based himself in Liverpool, going on to be a successful artist.[

Caunt was joined by former champion Tom Spring who had also moved to London running The Castle Inn at Holborn, where he arranged the patronage and contracts of many of the major boxing events of the period while overseeing fair play in the ring. He was not a similar boxer to Caunt though. He was more scientific and tactical in his approach.

The commissary was the experienced Tom Oliver. A man who knew how to put fights on.

Spring was not happy about the disorder at Newport Pagnell and was worried that the constabulary would find it too easy to interfere in Buckinghamshire, where Bendigo wanted to fight. Instead, he proposed Lillingstone Level, ten miles to the west, where Nick Ward and Deaf Burke had met in 1840.

Bendigo refused on the grounds that Caunt and his party were staying close by and it would be unfair for him to have to make a longer journey. After a heated argument, Oliver suggested a site further south, at Whaddon, which they believed to be in Oxfordshire. All parties agreed.

At first light on Tuesday 7th September, with a warm and dry day ahead of him, Tom Oliver and his assistant set off to set up a ring.

Keeper Of The Ropes

Tom Oliver had boxed in his younger days as ‘The Battersea Gardener’, having lost to Tom Spring. He took over the role of ‘keeper of the ropes and stakes’ on the death of the previous incumbent, Bill Gibbons. His knowledge and skill in staging prize-fights was legendary. He knew his way around the country, having travelled by gig, and later by rail, armed only with his sooty pipe and an Ordnance Survey map. He had scoured the landscape for a patch of turf suitable for the prize-ring’s finest to do battle. He knew the fields, inns and hamlets of almost every county boundary. Even at 56 years of age, he was still fit and athletic. It was said that he could still ‘leap a ditch or hedge and clamber through a gorse bush’ better than any younger man. Oliver was actually imprisoned the following year for being involved in another prize-fight.

On this particular morning, the movement of Oliver and his equipment did not go unnoticed. On his journey to Whaddon, he was soon followed by a procession of people ‘on the prad and toddle’ (horseback and foot). Oliver did not need this attention, as it would attract the blues and beaks (police and magistrates). He tried to escape from the head of the crowd by taking short cuts down narrow lanes and over fields, but was unsuccessful. By the time Oliver the ring had been erected at Whaddon, a crowd of five thousand had gathered. The Nottingham Lambs were already up to their tricks, ejecting people from their enclosure, unless they paid between one and five shillings for the privilege of being near the ropes.

Bendigo was by now at the ringside. He was later criticised for failing to prevent the excesses of his Lamb friends, but in the circumstances it would have taken a lot of energy to try, energy that he no doubt felt better saved for fighting Ben Caunt.

Last Minute Hitch

Ben Caunt was nowhere to be seen though. While the huge crowd waited on that hot afternoon, Caunt was still at The Cock Hotel in Stony Stratford. A constable had visited his team and informed them that Whaddon was in Buckinghamshire, not Oxfordshire as Spring and Oliver believed.

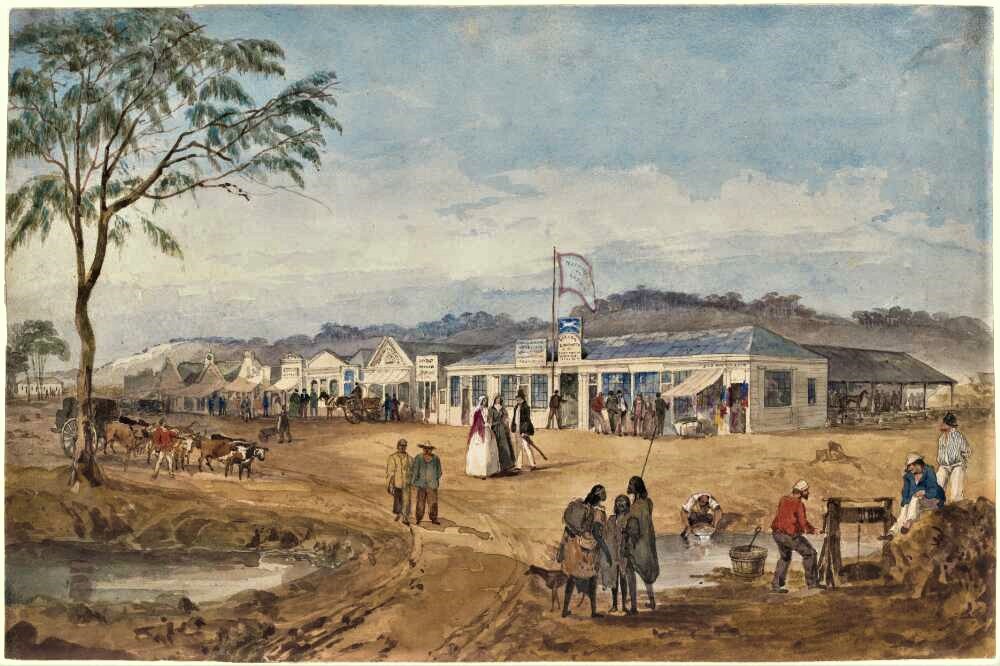

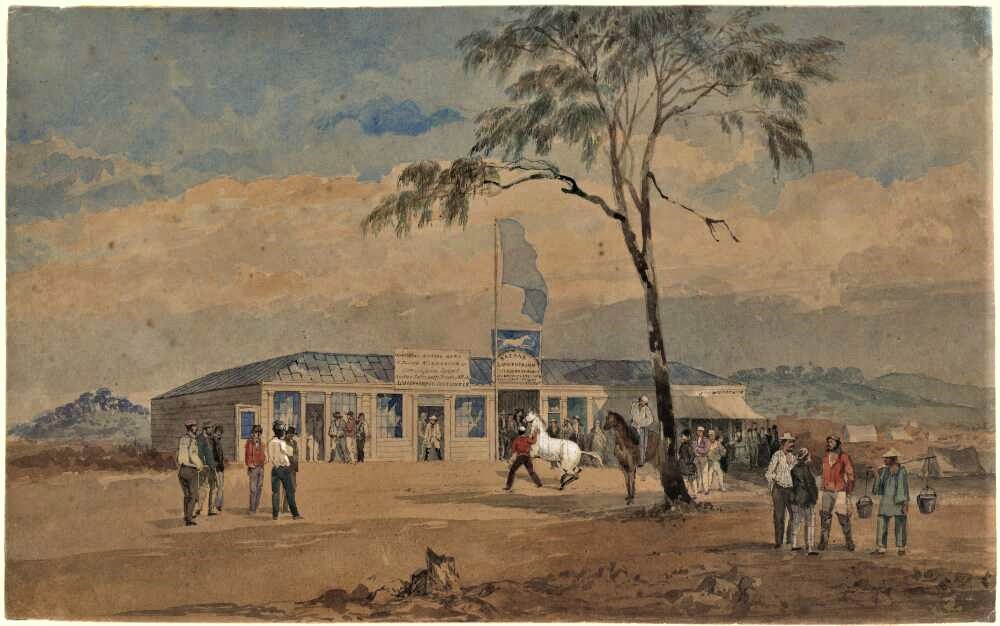

Bendy calls in at The Cock Hotel, at Stony Stratford, where Caunt was based prior to their fight.

The Cock Hotel at 72/74 High Street, Stony Stratford was built in the 18th century, and in its heyday was one of the important coaching inns along the the old Roman Road, Watling Street. It received up to 20 coaches a day through the carriage arch, and provided stabling and facilities for change of horses as well as sustenance for the travellers.

Caunt had been told that if they tried to stage the fight, he would arrest them. The Buckinghamshire magistrates were determined to prevent the fight at all costs.

A messenger on horseback was sent with a letter to Whaddon, but his news was greeted with scorn by Bendigo’s followers. They refused to allow him near Oliver and ripped up the letter he had brought from Spring. They wanted to remain where they were and were not about to give up their profitable enclosure and set off another trail round the countryside on the word of one man on a horse.

The situation was now becoming ludicrous. Five thousand people were waiting at Whaddon. Bendigo was ready but Caunt was miles away. No matter how much the Lambs disliked the idea of moving, there could be no fight without the ‘Big `Un’.

Eventually, a new site was agreed. It would be near the village of Lillingstone Level in Oxfordshire, the place Caunt had first proposed. The exact location, close to the Northants, was known for staging local prize-fights. It was called Sutfield Green.

Tom Oliver now led a second procession another eight miles. Bendigo was annoyed, and he blamed Ben Caunt for the chaos. Along the road, when his pony and trap passed the Big ‘Un’s party he shook his fist at the champion and swore to punish him. It was irritation Caunt did not need, rolling along a dusty road on such a hot afternoon.

At half past two, Oliver began to erect a second ring with an outer and inner enclosure. The crowd, which now numbered ten thousand or more, was becoming dangerously impatient.

When Caunt and Bendigo both arrived, unruliness broke out all around. Spectators struggled to find positions where they could see. Their tempers worsened by the heat and frustrations they had endured to be there. A large contingent of Nottingham Lambs dashed into the inner ring, swinging cudgels and forcing back all those not in possession of tickets purchased earlier. The stewards were men from the London Fancy. Most of them were ex-fighters and although armed with sticks and bull-whips, they were left powerless. The Lambs were organised and when the crowd were distracted by the arrival of the combatants, they took their chance.

No one was spared, whatever their status. A party of wealthy Londoners known as ’Corinthians’ had been promised tickets by Tom Spring, but he had not yet arrived. They tried to assert their upper class authority only to be jostled and beaten without fear or favour. The Nottingham Lambs did not hold with airs, graces or social status. At times like this a cudgel was more useful than a public school accent.

Bendigo, standing close by, lapped up the cries and good wishes of his supporters, without attempting to interfere. He had a bigger battle to fight.

In addition to the last minute confusion, neither side had agreed on a choice of referee.

Fortunately, George Osbaldiston, known throughout England as “t” Auld Squire.” who had retreated to his carriage to escape the crush. He finally consented to serve and the battle was declared on.

At twenty past three the fighters finally entered the ring.

Worldwide Attention

In the United States of America, the Nebraska Chronicle newspaper later reported on the fight:

The men presented a remarkable picture of manly and athletic grace as they advanced to the mark. Caunt was six feet two and a half inches in height and trained to a point he had never before equalled. He was nothing but bone and sinew, a hard hitting, bruising lion of a man, with an arm like a swinging beam and built like a windmill.

Nebraska Chronicle

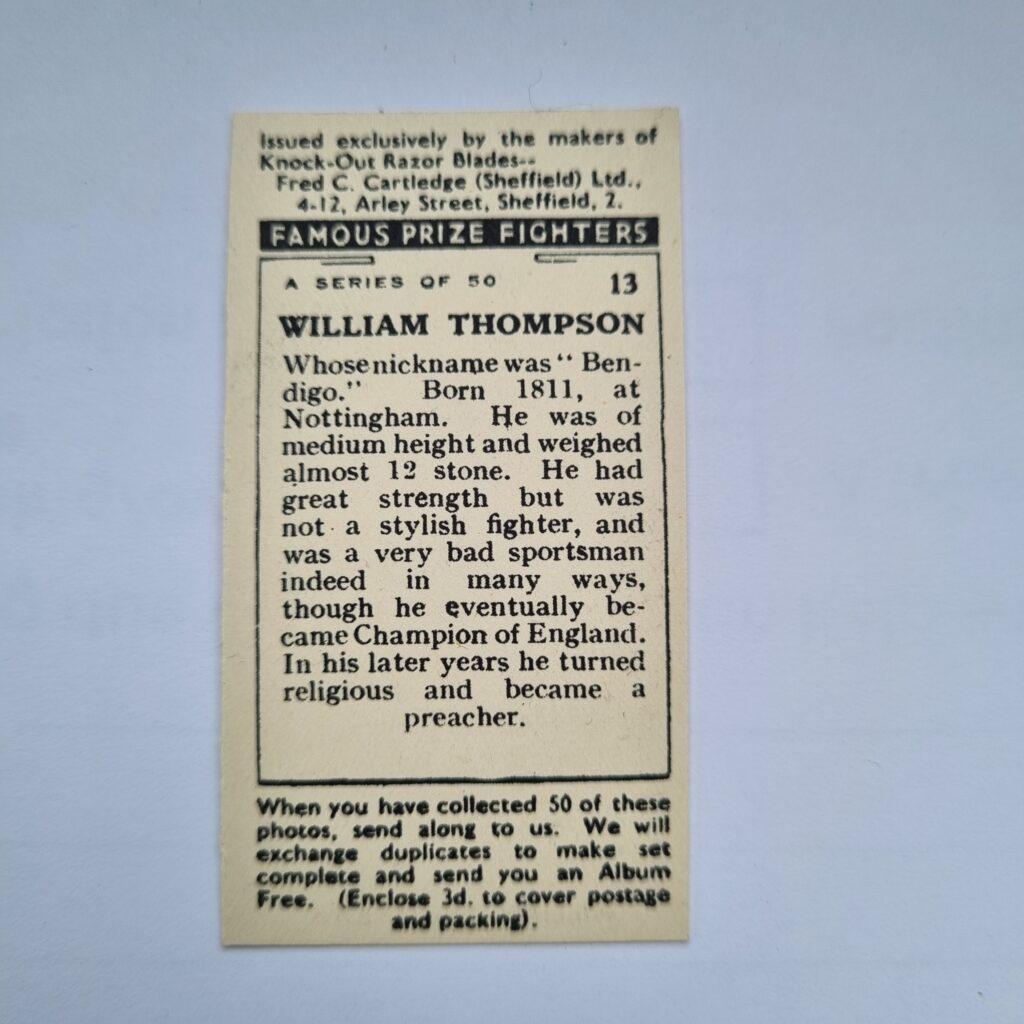

Bendigo, slender but compactly formed, was about five feet ten inches in height and weighed 169 pounds. He dragged his left leg slightly, part of the after effects of an injury received while skylarking which had once effectively shelved him. Save for this, he was a handsome, rugged figure.

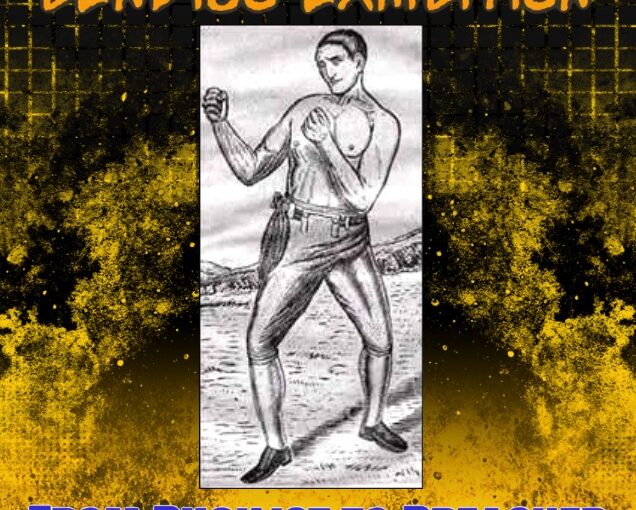

‘In his attitude Caunt showed little science, standing erect, with feet near together. Bendigo kept his right foot well advanced and brought his fists up and close with head back, they came together smiling, Bendigo opening the usual fire of jests with a humorous greeting and Caunt responding easily, then after touching hands, both snapped on guard.

Bendigo flew instantly into his tactics, all bounce and dash, hopping in and dancing out, feinting here, there and here again like a shadow boxer. Caunt knew his man and waited for his chance, suddenly letting out with a humming left swing. Bendigo ducked and grinned like an imp, tapping in lightly to the body with left and right, getting out again, and acting altogether like a mischievous schoolboy.

Caunt went after him doggedly and swung again, when Bendigo, coming under his guard, smacked him hard under the left eye. Caunt drove wildly and the challenger repeated the blow, opening an old scar on Caunt’s cheek and drawing first crimson.