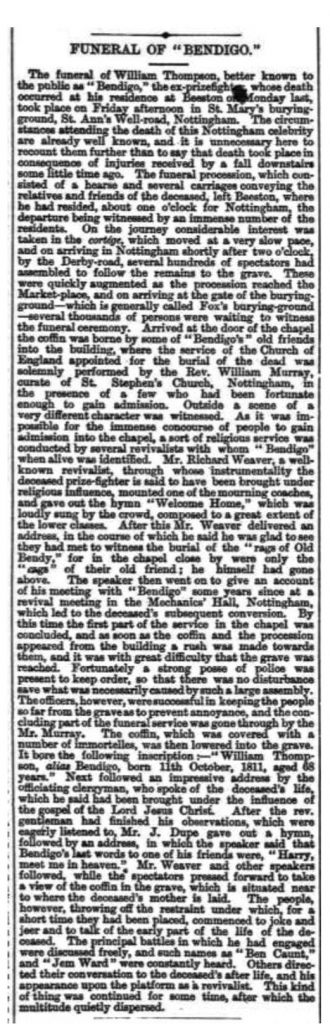

We have more information about the grave of Mary Thompson, Bendigo’s mother. She is not in the same plot as Bendigo, but actually in an entirely different cemetery.

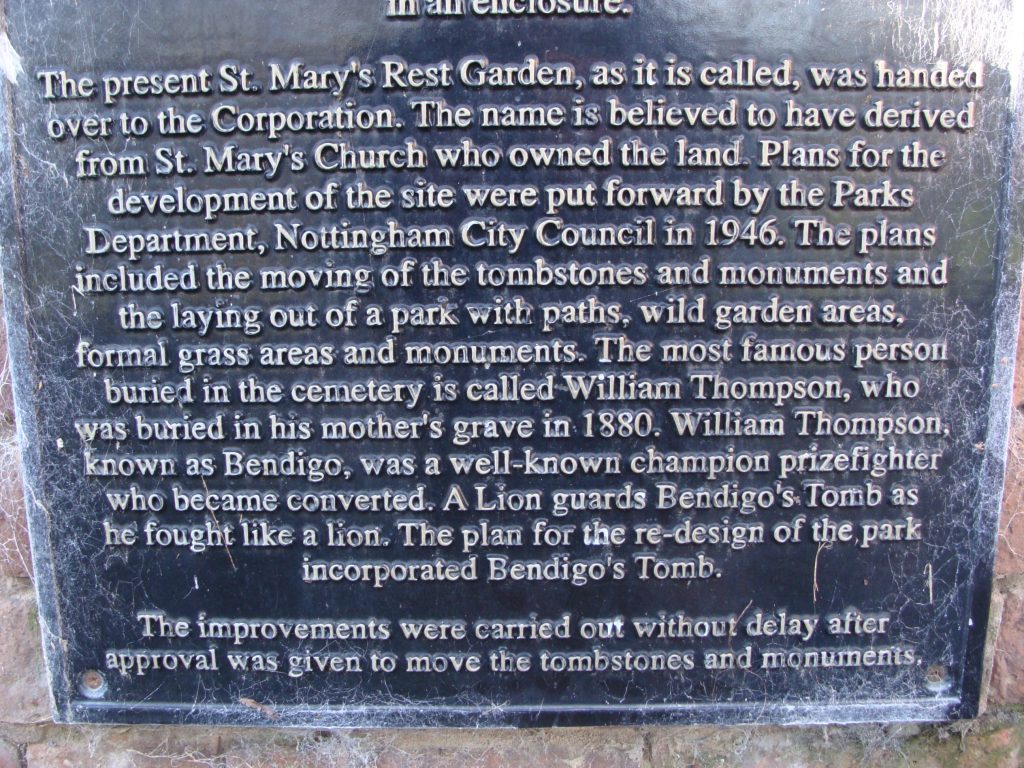

Below is a photograph of a plaque, which is near to Bendigo’s grave. The information on the plaque is incorrect.

Not only that, we have also discovered some interesting names to add to the Bendigo story.

Thanks to Scott Lomax (the archaeologist for Nottingham City Council) for pointing us in the right direction, literally.

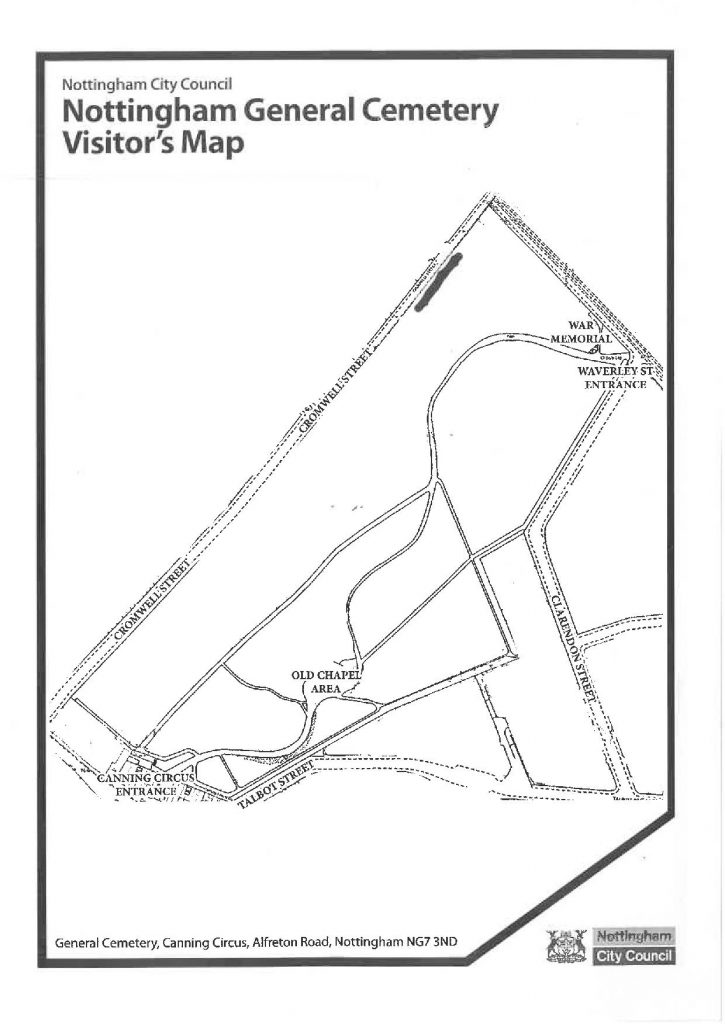

He has located the grave of Mary Thompson, and provided this plan of Nottingham’s General Cemetery to assist us in finding it.

The Thompson family.

Bendigo’ parents were Benjamin Thompson and Mary Levers. They married at St Mary’s Church in Nottingham in 1805 and had the following children.

Rebecca Thompson – born in 1805. Nothing more is known about her.

Thomas Thompson – born in 1807. We know that Thomas had two sons Benjamin and William.

John Thompson – born in 1809. John became a respected optician in Nottingham. We do not believe he married or had any children.

William and Richard Thompson – born in 1811 as triplets, with the third child (James) not surviving the birth. Richard died a week later. Maybe this created the bond between William and his mother, a bond that was never broken.

Mary Thompson – born in 1815. Mary died as a child in 1818.

Why is it important to identify the grave of Bendigo’s mother?

Mary Thompson had a huge influence on his life. We must remember that not only was Bendigo the only triplet to survive, his father died when Bendigo was 15 years old. Both Bendigo and his mother ended up poverty stricken and spent time in the workhouse.

As Bendigo developed his reputation as a prize-fighter, he remained close to his mother.

She is known to have encouraged him to take on Tom Paddock for his final fight in 1850. As a 39 year-old, Bendigo was in two minds as to whether to accept the fight or not. His 82 year-old mother encouraged him by saying:

“I tell you this Bendy, if you don’t take up the fight you’re a coward. And I tell you more, if you don’t fight him, I’ll take up the challenge myself.”

Mary Thompson

Bendigo won the fight. He then retired undefeated as champion, with two prize belts and four silver cups to his name, perhaps the last of the great prize-fighters.

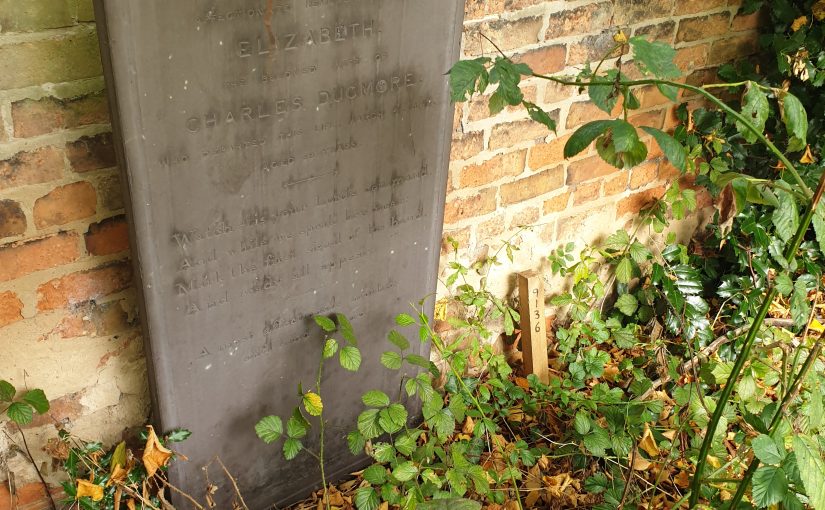

Whilst there is no headstone on Mary Thompson’s grave, the records show that Bendigo’s older brother Thomas is also buried there.

He is buried in the plot next to Mary. Thomas was buried there on 27th December 1863, aged 57 years. He was described as an engineer. He is interred in plot 9137 with an Elizabeth Thompson and Eliza Proctor.

What do we know about those buried with Thomas Thompson?

We know that Thomas Thomson had two sons by his first wife. He had moved to Sheffield in Yorkshire. Thomas’ second son (also named William) was charged but acquitted of his wife’s manslaughter in 1876.

Thomas appears to have returned to Nottingham. His second wife was previously known by the name Elizabeth Yates. We know that Bendigo was friends with a man called George Yates. He and George used to go fishing together. This helps to show that the family as a whole remained close. We know nothing more about Eliza Proctor.

Bendigo’s other brother, John Thompson was buried in the Rock Cemetery in 1873 aged 64 years. He is buried on his own in plot 1292.

General Cemetery – How To Find The Grave Of Mary Thompson

Here are a sequence of photographs which will take you to Mary Thompson’s grave.

Why did the family use several burial grounds?

You have to remember that in those days the church was far more influential in society, than today. Also burials were the norm. Cremations didn’t come in until the 1880s.

Nottingham’ main church was St Mary The Virgin Church on High Pavement in what is now known as Nottingham’s historic Lace Market.

With the development of the lace and textile trade, the population of Nottingham had increased dramatically. The area around St. Mary’s Church changed too.

This expansion brought with it many problems, not least of which was where to bury the dead. The parish church yard rapidly began to run out of space and it was decided new burial grounds were needed. Between 1742 and 1813 three new cemeteries were created on land around Barker Gate, near the church.

By the time of Bendigo, even these burial grounds were becoming full. Ordinary people would rarely pre-arrange a family plot. Burials were arranged the most convenient cemetery available.

Bendigo himself is buried at a former cemetery on Bath Street. This was created in 1935, after a Quaker by the name of Samuel Fox donated the land, after an outbreak of cholera in 1835.

The Nottingham General Cemetery Company was opened by Royal Assent for their Act of Parliament on 19 May 1836. The site covers 18 acres which is on a slope. The lower entrance is on Waverley Street (opposite the Arboretum) and then rises up to the cemetery gatehouse and alms-houses at the top entrance of Sion Hill, now Canning Circus. When the cemetery was opened, a single grave cost 7s 6d (equivalent to £34 in 2019). It stopped allocating new plots in 1923. The freehold passed to Nottingham City Council in 1956. The mortuary chapels were demolished in 1958.

The General Cemetery contains the war graves of 336 Commonwealth service personnel and one Belgian war grave from World War I. Most of those buried there had died at military hospitals in the city. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission continue to maintain the graves. One of the notable people buried here in 1888, is Samuel Morley VC. Morley was awarded the Victoria Cross, not once, but twice.

Nottingham’s Church or Rock Cemetery was not opened until 1856, and was not an option for the burial of Mary Thompson.

St Mary’s Church was also responsible for the Nottingham workhouse from 1726. This was the same workhouse where Bendigo and his mother were sent in around 1827. The church continued to manage the workhouse until 1834, when responsibility was transferred from parishes to secular Boards of Guardians. The workhouse was demolished in 1895 to clear part of the site needed for the construction of the Nottingham Victoria railway station.

More Churches For Nottingham

As Nottingham expanded, St Mary’s created further parishes, including the Holy Trinity Church near to Bendigo’s birthplace. It is worth noting these, to show the influence that the Anglican Church had in society.

1822 St Paul’s Church, George Street, Nottingham.

1841 Holy Trinity Church, Trinity Square.

1844 St John the Baptist’s Church, Leenside (destroyed by bombing in May 1941).

1856 St Mark’s Church, Nottingham.

1856 St Matthew’s Church, Talbot Street.

1863 St Ann’s Church, Nottingham.

1863 St Luke’s Church, Nottingham

1863 St Saviour’s, Arkwright Street

1864 All Saints’, Raleigh Street, Nottingham.

1871 St Andrew’s Forest Road, Nottingham.

1881 Emmanuel Church, Woodborough Road.

1888 St Catharine’s, St Ann’s Well Road, next to St Mary’s Rest Garden on Bath Street.

1903 St Bartholomew’s Church, Blue Bell Hill Road.

Thank you for reading.

We hope to find out more details, and update you.