On Sunday 23rd August 2020, supporters of the Bendigo Heritage Project walked the route of Bendigo’s funeral cortege in 1880.

The group went from the site of his former home at Wollaton Road in Beeston to his grave at Bath Street in Nottingham City Centre, a distance of 5.7 miles.

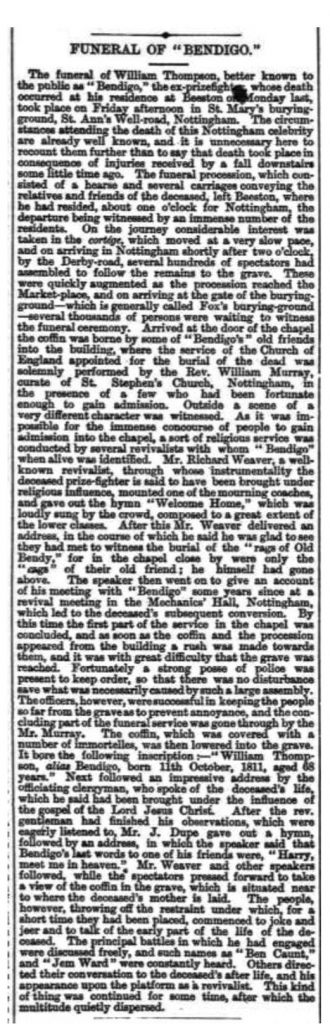

Here’s what the Nottinghamshire Guardian reported on 3rd September 1880.

The funeral of William Thompson, better known to the public as ‘Bendigo’, the ex prize-fighter, whose death occurred at his residence at Beeston on Monday last, took place on Friday afternoon in St Mary’s burying ground, St Ann’s Well Road Nottingham.

The circumstances attending the death of this Nottingham celebrity are already well known, and it is unnecessary here to recount them further than to say that death took place in consequence of injuries received by a fall downstairs some little time ago.

The funeral procession, which consisted of a hearse and several carriages conveying the relatives and friends of the deceased, left Beeston at one o’clock for Nottingham, the departure being witnessed by an immense number of residents.

On the journey considerable interest was taken in the cortege, which moved at a very slow pace, and on arriving in Nottingham shortly after two o’clock, by the Derby Road, several hundreds of spectators had assembled to follow the remains to the grave. These were quickly augmented as the procession reached the Market-place, and on arriving at the gate of the burying ground – several thousands of persons were waiting to witness the funeral ceremony.

Arrived at the door of the chapel the coffin was borne by some of Bendigo’s old friends into the building, where the service of the Church of England appointed for the burial of the dead was solemnly performed by the Rev. William Murray, curate of St Stephen’s Church, Nottingham, in the presence of a few who had been fortunate enough to gain admission.

Outside a scene of a very different character was witnessed. As it was impossible for the immense concourse of people to gain admission to the chapel, a sort of religious service was conducted by several revivalists with whom Bendigo when alive was identified. Mr Richard Weaver, a well-known revivalist, through whose instrumentality the deceased prize-fighter is said to have been brought under religious influence, mounted on of the mourning coaches, and gave out the hymn Welcome Home, which was loudly sung by the crowd, composed to a great extent of the lower classes. After this Mr Weaver delivered an address, in the course of which he said he was glad to see they had met to witness the burial of the ‘rags of Old Bendy’, for in the chapel close by were only the ‘rags’ of their old friend; he himself had gone above.

The speaker then went on to give an account of his meeting with Bendigo some years since in the Mechanics Hall, Nottingham, by which led the deceased’s subsequent conversion. By this time the first part of the service in the chapel was concluded, and as soon as the coffin and the procession appeared from the building a rush was made towards them, and it was with great difficulty that the grave was reached.

Fortunately a strong posse of police was present to keep order, so that there was no disturbance save what was necessarily caused by such a large assembly. The officers, however, were successful in keeping the people so far from the grave as to prevent annoyance, and the concluding part of the funeral service was gone through by Mr Murray. The coffin, which was covered with a number of immortelles, was then lowered into the grave. It bore the following inscription: William Thompson, alias Bendigo, born 11th October 1811 aged 68 years.

Next followed an impressive address by the officiating clergyman, who spoke of the deceased’s life, which had been brought under the influence of the gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ. After the Rev gentleman had finished his observations, which were eagerly listened to, Mr J Dupe gave put a hymn, followed by an address, in which the speaker said that Bendigo’s last words were, ‘Harry, meet me in heaven’. Mr Weaver and other speakers followed, while the spectators pressed forward to take a view of the coffin in the grave, which is situated near to where the deceased’s mother is laid. The people however, throwing off the restraint under which, for a short time they had been placed, commenced to joke and jeer and to talk of the early life of the deceased. The principal battles in which he had engaged were discussed freely, and such names as ‘Ben Caunt’, and ‘Jem Ward’ were constantly heard. Others directed their conversation to the deceased’s after life, and his appearance upon the platform as a revivalist. This kind of thing continued for some time, after which the multitude quietly dispersed.